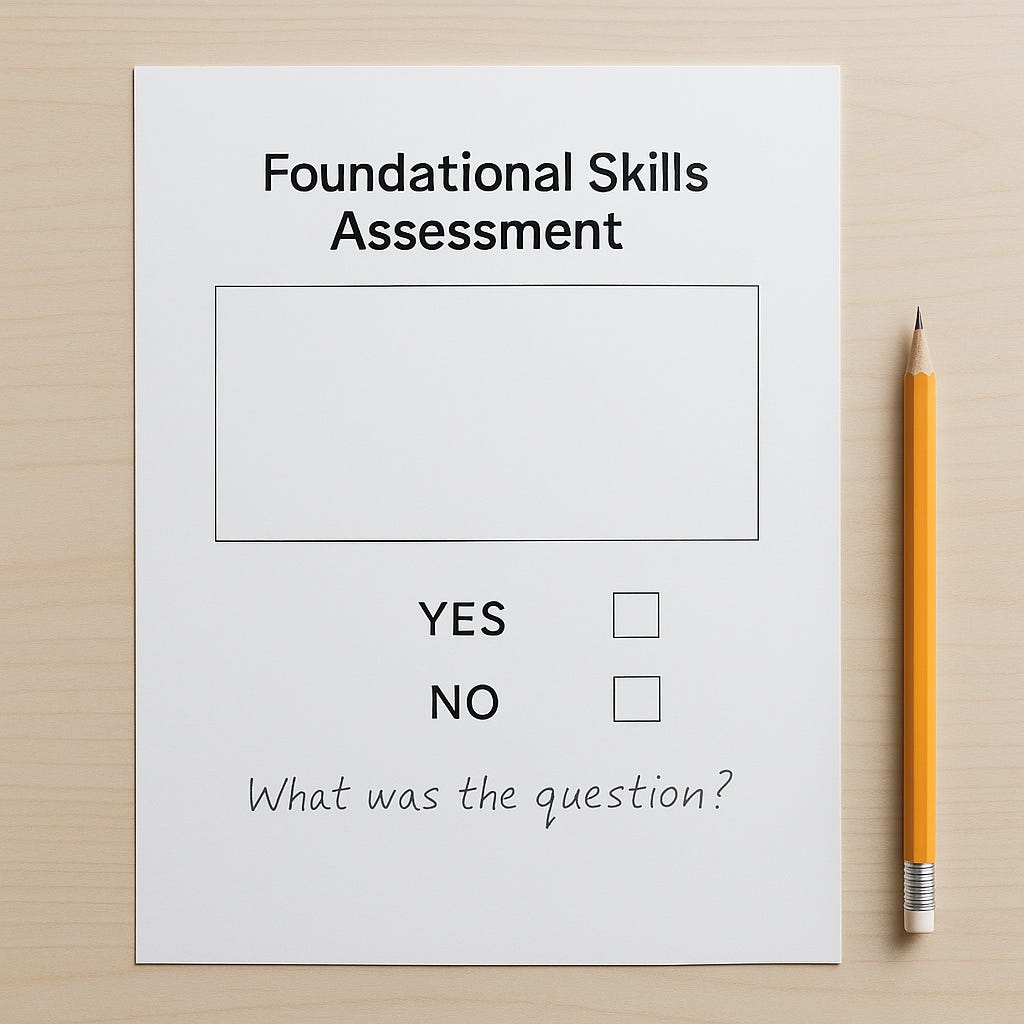

Why Are Kids Still Writing the Foundational Skills Assessment (FSA)?

What are measurable results after 25 years of a "low-stakes experiment"?

By a parent who still believes in public education.

The week my inbox turned into policy theater

First came the official letter from the school: a cheery explainer that my child will soon write the FSA—our province‑wide measure of literacy and numeracy. Lots of promises about “valuable information,” “guiding improvements,” and “assurance” that learning is on track. Zero examples of improvements achieved, zero trend lines, zero “because of the FSA we did X and Y improved by Z.”

Then came two printed flyers from the BC Teachers’ Federation. These politely urged me to excuse my child. Their argument: the FSA isn’t useful for individual students, it nudges teaching toward test prep, the data gets misused in public rankings, and it rarely brings resources to the kids who need them most.

So there I was—the parent in the middle—asked to arbitrate a 25‑year disagreement with my child as the chess piece.

A 25‑year experiment, by design

The Foundation Skills Assessment launched around the turn of the millennium as a low‑stakes, province‑wide checkup. The idea sounded sensible: ask every Grade 4 and 7 student the same set of literacy and numeracy questions once a year, then look for patterns across districts and demographics. If results fall in certain areas, direct attention there. Over time, build a long, stable data series that helps leaders steer the system.

I like sensible ideas. I also like evidence.

Which is why it’s jarring that, a quarter century later, the public‑facing “Information for Parents and Caregivers” still offers promises in the future tense—guides improvements, supports decision‑making, ensures standards—without showing the past tense: what actually changed because of this test.

If a program runs for two and a half decades, the bar isn’t, “Here’s what this tool is for.” The bar is, “Here’s the measured impact this tool has had, year by year, and here’s what we changed because of it.”

What the teachers sent me

BC Teachers’ Federation (BCTF) pamphlet argues:

The FSA is not useful to students or teachers.

Classroom assessments already provide better, more timely feedback.

Large‑scale, broad tests can distract from deep learning and encourage short‑term thinking (“What’s on the test?”).

Results are misused to rank schools and, indirectly, neighbourhoods.

Reasonable claims. But claims all the same. So I went looking for two things:

Clear examples of system‑level action the Ministry took because of FSA results (not just inferences).

Credible evidence that FSAs improved student learning across B.C. in ways we can measure and attribute.

What I can easily find (and what I can’t)

I can find a meticulous, 31‑page marking‑reliability report. It confirms that teachers around the province score the same written responses in nearly the same way (“within one point”). Good. Alignment matters.

But alignment in scoring is not impact in learning.

When I look for public evidence tying FSA data to actions taken and results achieved, here’s what turns up:

District‑level planning documents: Some districts cite FSA trend lines in “Enhancing Student Learning” reports to justify hiring numeracy coaches, adding literacy supports, or focusing professional development. That’s encouraging. It’s also mixed, piecemeal, and rarely causal. The reports usually present the FSA as one data source among several, not the reason an intervention worked.

Public dashboards: The province hosts pages where you can explore FSA performance by district and school. These are helpful for seeing patterns (e.g., gaps by subpopulation). What they don’t do is close the loop. There’s no “because of this pattern, we did X in 2016; here’s what changed by 2019 in the same cohort.”

Independent research: A handful of studies find small, subgroup‑specific effects from low‑stakes testing—nothing to suggest the FSA has been a province‑wide engine of improvement. If there’s a dramatic success story, it’s hiding behind a paywall or it doesn’t exist.

So after 25 years, the public record feels like this:

We have lots of data (mostly snapshots, some trends).

We have consistent marking (good craft).

We don’t have a clear, public chain of impact from FSA → action → improved outcomes—at scale, with attribution and time stamps.

If you run a system‑wide assessment for a generation of children, you owe the public more than assurances. You owe a ledger of decisions and results.

What the letters don’t say—but the market knows

There’s an uncomfortable side effect no one talks about in official letters. FSA results feed school “report cards” that are eagerly repackaged for homebuyers. Real estate agents advertise catchments with “top ranked” schools. Prices respond. Families with means sort into the most coveted zones, reinforcing the very advantages that produce high scores. Lower‑ranked schools bear the reputational cost, even when they’re doing heroic work with more complex needs.

Whatever you think about standardized tests, it’s hard to argue the FSA has been neutral in the housing market. The data was meant for stewardship; much of it became marketing.

What a real impact story would look like

Imagine, for a moment, that the FSA has been quietly effective. That somewhere in the Ministry’s vault sits a time‑series of actions and outcomes that would make any skeptic nod.

It would read like this:

2005: FSA shows a province‑wide dip in early numeracy in districts A, B, and C. Ministry funds targeted coaching in strategies P and Q; districts deploy resource‑teacher teams to 28 schools.

2007: Cohorts that received support show a 9–12 point rise in the “on track” band in Grade 4 numeracy, sustained in Grade 7; gains are larger for students who started “emerging.”

2010: We expand the pilot to 14 more districts; after three years, we see a 6‑point lift province‑wide and a narrowing of gaps for identified subpopulations.

2014–2018: We refine the rubric to capture mathematical reasoning, not simply right answers. The change explains a temporary shift in trend lines (documented here), and then stabilization at a higher level by 2019.

2021 onward: We publicly discontinue interventions that didn’t move the needle and double‑down on those that did, with cost‑effectiveness figures attached.

That is what a quarter‑century impact narrative looks like: signal → response → measured change → iteration.

If that story exists, publish it. If it doesn’t, let’s stop pretending the existence of a dataset equals the use of a dataset.

“Low‑stakes” isn’t the shield we think it is

Defenders of the assessment often remind us the FSA is “low‑stakes.” It doesn’t affect grades; it isn’t supposed to rank schools; it’s just one data point. All true. But low‑stakes for whom?

For students, the stakes are emotional and instructional: a week reshuffled; a classroom tone that inevitably shifts. Some kids thrive on tests; others freeze.

For teachers, the stakes are reputational: even when the Ministry disavows rankings, rankings appear anyway.

For parents, the stakes are interpretive: we’re asked to make sense of a system signal without the system’s own verdict on what it changed.

Low‑stakes assessments still have high‑stakes consequences when they ripple into real life without a stewarded narrative.

The parent’s paradox: agency without authority

As a parent, I can choose to let my child write the FSA or to excuse them—in our case, my child wants to write it, and I respect that. I’ll frame it as practice in trying new things, not as a judgment of ability. But whether kids write or not is a micro‑decision in a macro‑system that keeps asking families to referee an institutional disagreement it hasn’t resolved internally.

Parents are given agency without authority. We can sign the form, but we can’t see the ledger.

What a better bargain could be

I don’t need the Ministry to end all standardized testing. I need the Ministry to make the bargain explicit and evidence‑based:

Publicly close the loop. For every five‑year window, publish a plain‑language “FSA to Action to Outcome” report: what patterns we saw, what we did, what changed, what didn’t, and what we learned. Include costs.

Stop outsourcing the narrative. If you disavow rankings, fill the vacuum with the story that actually helps learning. Tell us how educators used the data, not how realtors used the headlines.

Pilot smarter, publish sooner. If the FSA reveals a problem, pilot a response within a school year, evaluate within two, and publish within three. Twenty‑five years is too long to promise results you never show.

Protect classrooms from drift. Pair any province‑wide assessment with an equal investment in professional time for classroom‑embedded assessment that actually moves learning forward.

What I will tell my child

When my children sit down to the FSA, I will tell them this isn’t a measure of their worth or a label that will follow them. It’s a snapshot. I will also tell them that grown‑ups have been running this snapshot for 25 years, and the most important question we can ask of any ritual is: Does it change what we do next?

If the answer is yes, we should all be able to see it.

If the answer is no, then let’s have the courage to redesign the ritual—or stop performing it.

A note to the Ministry (and to the Federation)

You both say you want what’s best for kids. So start by sparing them the crossfire of dueling letters. Meet each other where the public is: show us the chain from signal to change to result. If the FSA is working, we’ll cheer. If it isn’t, we’ll help you build something better. But don’t ask us to referee your disagreement with our kids’ time.

Until then, parents will keep doing what we always do: showing up, reading the fine print, and asking the awkward question in the subject line—Why are kids still writing this test, and what measurably changed because of it?